Shaws Cove Ship Wreck

Finding the origins of this prominent shoreline spectacle

October 2025 (researched and written by The Dogfish)

Between Green Point, south of Horsehead Bay, and Shaws Cove off Arletta lies a sand spit with a very obvious shipwreck. The wreck is easily visible from the DeMolay Sandspit Nature Preserve (Bella Bella Beach) if you know what to look for. It raises an obvious question that is typically answered with: “It was just an old barge.” Although it may have once served as a barge, the history of this wreck is much more interesting.

Looking at maps and charts, the wreck seems to appear between 1943, where it is absent, and 1953, where it is clearly marked on the USGS map. A 1956 Tacoma News Tribune article addressing this wreck is consistent with it appearing on the beach sometime in the late 1940s or early 1950s. What remains is a heavy wooden structure consisting of large beams with bolts and a central spine holding it together. The structure is about 200 feet long and is generally above the high tide line, although driftwood conspicuously sits on top from extreme high tides and storms. Note: the sand spit is private property—you may look, but not touch without permission.

The Story

The ship’s story starts in 1917 when, faced with the threat of German U-boats during World War I, the United States initiated construction of as many inexpensive freighters as possible to carry cargo to Europe. This was the same strategy that later produced Liberty Ships in World War II, but in WWI many varied designs were attempted, including wooden freighters that could be built inexpensively by small legacy shipyards across the country. One of these designs was the “Ferris ship,” officially Ferris Design 1001.

A significant number of Ferris ships were built, though most were never used for their intended purpose. Many were only partially completed—missing key components such as engines—before being sold for salvage. By the early 1920s, a large group of these were moored in Lake Union under ownership of a local salvage company. This is where the story becomes muddled: various conflicting accounts and citations arose around these ships in South Puget Sound. Historian Chris Ehrlich, a Gig Harbor–based curator, clarified much of the confusion in her blog (Ehrlich's 2018 blog post carefully cites evidence showing the ships were improperly documented in a commonly cited photo as Foundation Schooners). The following brings together her information, additional details from the 1956 Tacoma News Tribune interview with Alva McKinley, and further research to confirm the Ferris Ship design matches the Shaws Cove wreckage.

Burning Ships at Minter Creek

Ehrlich documents how the Washington Tug and Barge Company towed the salvage Ferris ships to Henderson Bay in order to burn them and recover the steel components. In 1956, Alva McKinley gave a first-hand account to the Tacoma News Tribune:

“The ships were towed here and on the high tide were pulled as far onto the beach as possible, then tied together and intentionally set on fire. As the wood burned, the pieces of iron dropped to the bottom, and scows were towed in and anchored so that they would ground with the falling tide.

The iron was then picked up and loaded onto the scows, which were, on the next high tide, taken away and towed to Seattle. The job of burning and towing went on for several months and, so far as I know, proceeded smoothly without unexpected incidents.

From my home on Horsehead Bay, about eight miles distant, I could see the light at night and more in the daytime while the burning was going on. I was over there twice during that time…. Several days later, seeing smoke arising from the burning ground, I went over again. Fourteen ships were burning.”

Quite a few ships were destroyed in this way, each successive group pulled up on the beach and anchored. The last set, though, had an interesting epilogue that explains the Shaws Cove wreck. Alva continues:

“When the last group was burned, the bottoms were not destroyed but left on the beach tied with steel cables. These soon rusted away and the old ship bottoms were left to float away, which they did….”

She notes how they floated away, with some even passing through the Narrows into Commencement Bay. This created hazards to navigation, prompting government intervention. Alva finishes by explaining the particular wreck on the Shaws Cove sand spit:

“A government boat soon appeared and took charge. These wooden bottoms could not easily be sunk, so they were pushed up onto beaches in convenient places and tied with cables. That is how this particular ship came to be where it is. It was found floating in the immediate vicinity and beached on the sand spit as the nearest and most convenient place. It is there yet and will stay there many more years, as long as any of it remains.”

A Ferris Ship?

From the water, the wreck looks like a flat barge, but aerial imagery reveals otherwise. A 1976 Washington State shoreline photo makes it even clearer this was once a ship. This is where confusion enters the narrative again, clarified by Ehrlich. Her article focused on the misidentification of a 1926 Minter photograph as showing Foundation Schooners. In reality, she documented that the photo shows Ferris Ships.

Identification is complicated because these vessels may not have been completed as full ships. Both Ferris Ships and Foundation Schooners were converted into freight barges and used in Puget Sound primarily for hauling logs (note the barge conversion on the far right of the Lake Union photo). The 1976 shoreline photo appears to show a bowsprit—characteristic of a Foundation Schooner, not a Ferris Ship. But this is misleading, as what remains is only the ship’s bottom. That protruding beam is the remains of a keelson, not the more delicate bowsprit, which would have been much higher and consumed by fire.

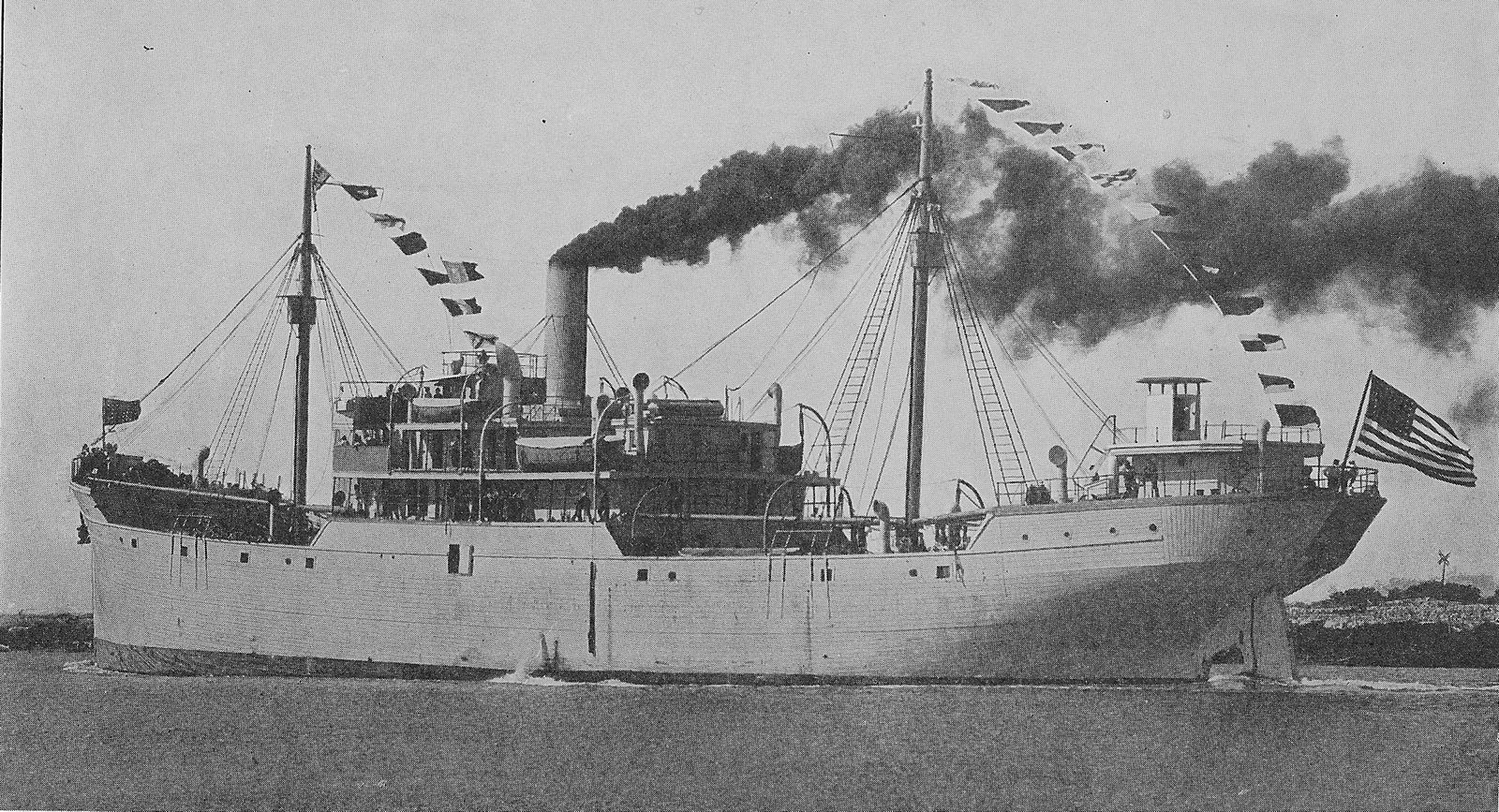

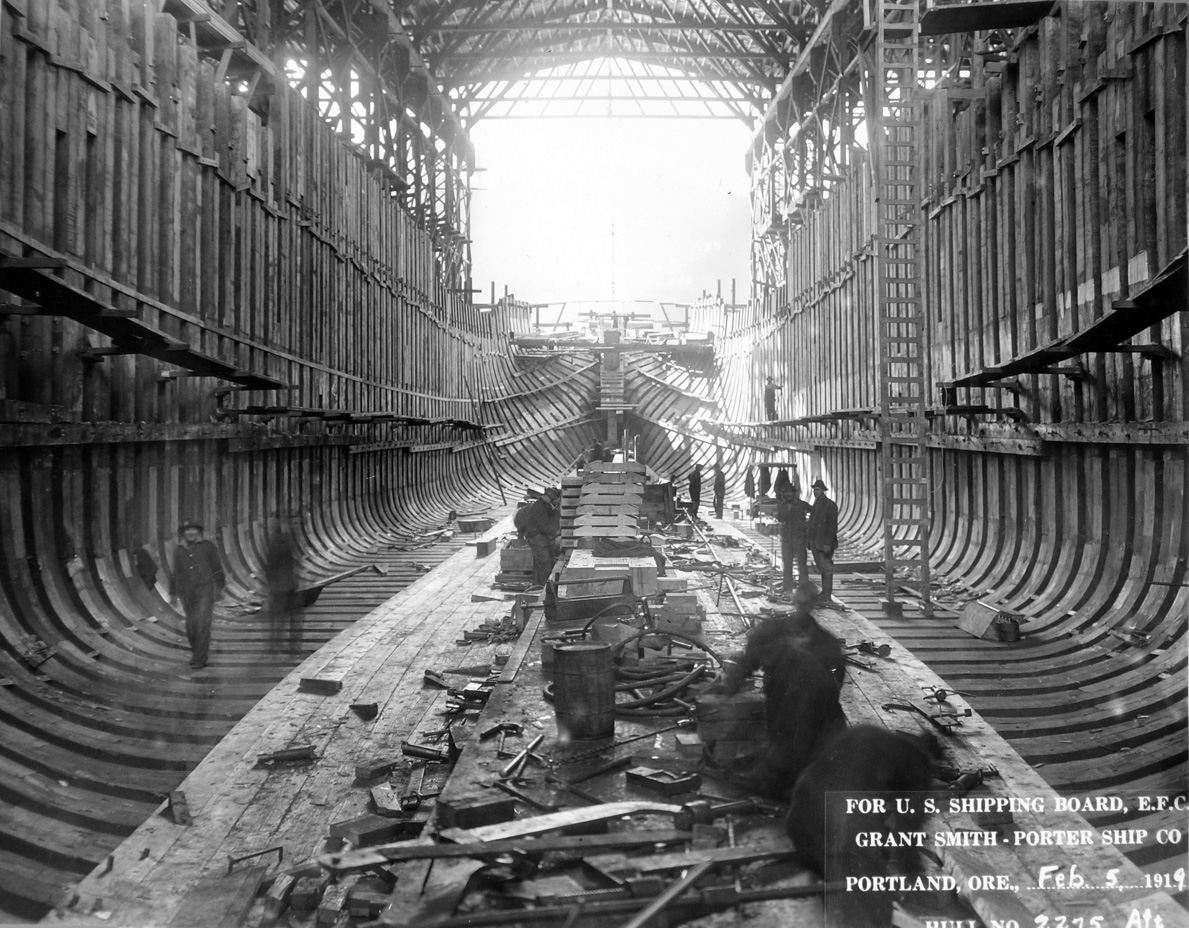

Ferris Ship plans are readily available for model shipbuilding. The “Frames-12” double-spaced 36-inch centers are completely consistent with the frames visible on the beach. The tall bolts running down the middle would have held the keelsons, now burnt or rotted away, in place. A photo showing a Ferris Ship–to–barge conversion in Portland neatly illustrates this original structure.

A Ferris Ship Indeed

Taken together, this evidence confirms the wreck is the bottom of a Ferris Ship burned for salvage at Minter Creek in the mid-1920s. The remains then sat for decades anchored to the shore until breaking loose in the late 1940s, drifting around South Puget Sound, and finally being intentionally beached on the Shaws Cove sand spit.

Notes: “Shaws Cove” is identified on a few maps, based on the name of adjacent landowners. In various places, the wreck is imprecisely described as “at the entrance to Carr Inlet,” incorrectly as “adjacent to Horsehead Bay,” or colloquially as “by the Moorlands.” I have chosen “Shaws Cove” to provide a precise reference point, though Green Point was also considered.