Ka-ka-als, Grave, Tanglewood

A name is important

November 2025 (researched and written by The Dogfish)

Dogfish note: The Dogfish typically refrains from telling Native American stories as those stories should be told by the people who own them. Exceptions are when there are fully documented Native American sources or when a story can be accurately told from sources that are generally agreed upon by Native American scholars. With that in mind, this story will always be open for correction or retelling from a voice of Indian people.

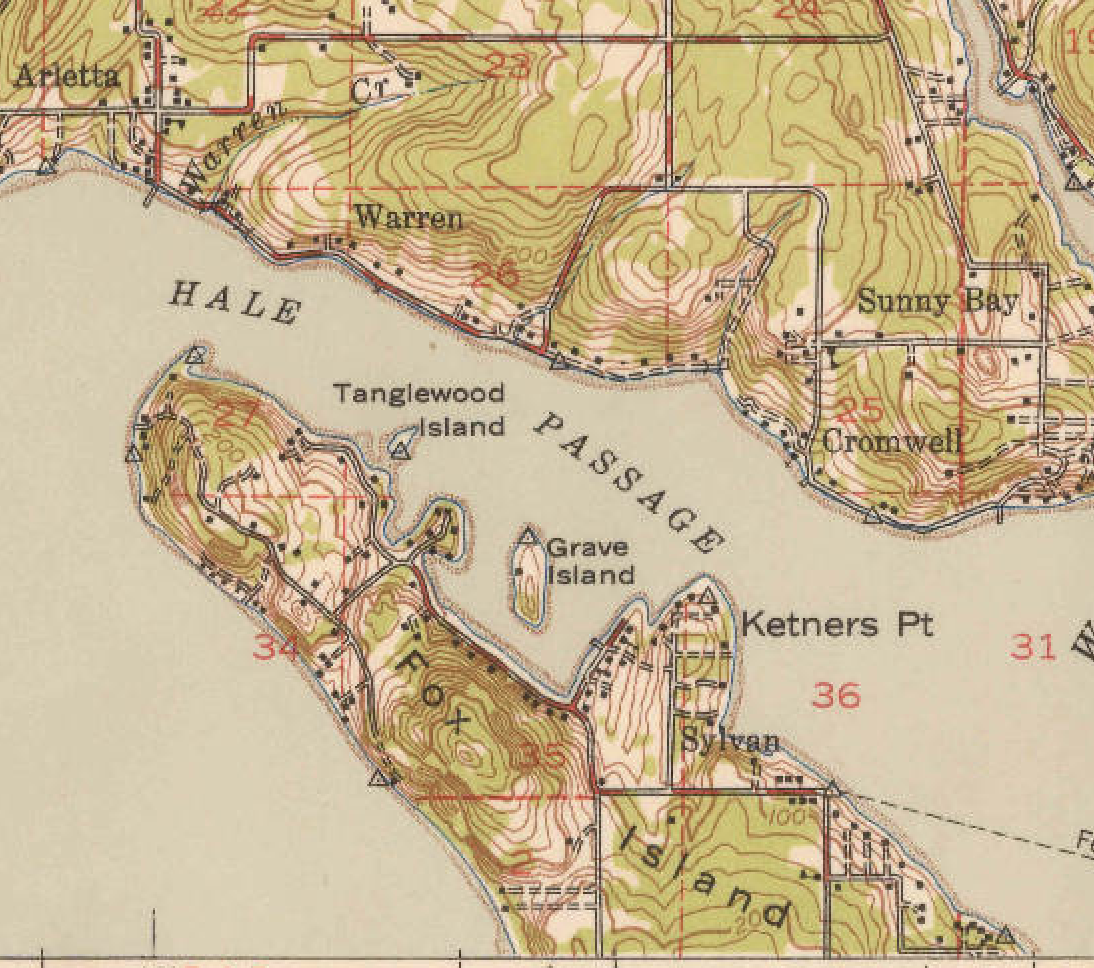

The 1942 USGS map looks different in many ways from today. At first glance, the most obvious change is the missing Fox Island Bridge (opened in 1954), but one will quickly notice that the nearby small islands have different names than today. Towhead Island is labeled “Tanglewood Island” and Tanglewood Island is labeled “Grave Island.” The 1947 Board on Geographic Names decision was the final step in the erasure of the Native American history associated with the tiny island known as Ka-ka-als.

Dogfish note: Cecelia Svinth Carpenter refers to Ka-ka-als as the name for the small island with graves off Fox Island. It is the only documented Native American name for the island found so far. The Dogfish activity seeks any corrections on what the name should be and, in the meantime, will defer to Carpenter’s exceptional credentials as an Indian historian in this matter.

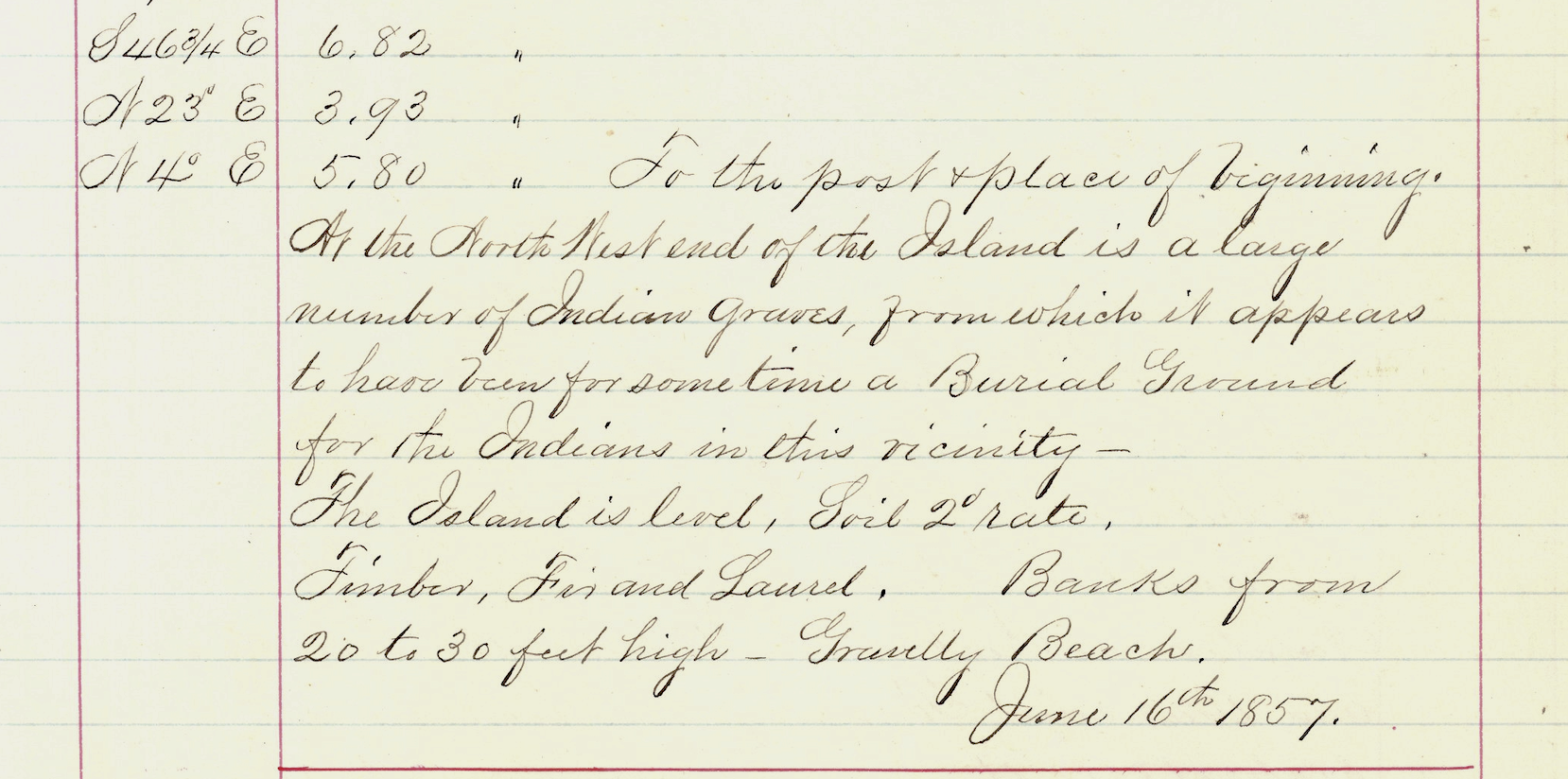

The island does not appear on either the Vancouver (1792) or Wilkes Expedition (1841; published 1847) maps. By the 1867 Coast Survey Chart, however, it is labeled “Grave Island.” During the 1850s a survey was conducted throughout Fox Island, Carr Inlet, and the Gig Harbor area. The surveyor logs—available in full online—document surveyors walking township and section lines, placing posts and flags, noting what they observed, and following shoreline “meanders.” On June 16, 1857, the surveyor recorded visiting Cutts Island and then “Grave Island”:

“At the North West end of the Island is a large number of Indian graves from which it appears to have been for sometime a Burial Ground for the Indians in this vicinity.”

There are a couple of key takeaways from this account. First, surveyors did not, nor do they now, name geographic features, so the island must already have been known locally as “Grave Island.” Second, the graves appeared to have been there for some time. As this survey was conducted less than a year after the Indian people interned on Fox Island had been forced to depart, it is highly likely this was a traditional burial ground—not simply the resting place of the eighty or more individuals who died during the internment.

A Detour to Cutts Island

This brings up an interesting side note on Cutts Island. Cutts Island is the small state park off Raft Island in Carr Inlet and locally referred to as “Deadman Island”. The island was originally named “Crow Island” by Peter Puget. In Meany’s 1923 Origin of Washington Geographic Names, he offers this minimal explanation about Cutts Island:

“Scott Island, a small island in Carr Inlet, in the northwestern part of Pierce County. It was named in honor of Thomas Scott, Quartermaster in one of the crews, by the Wilkes Expedition, 1841… The name has since been changed to Cutts Island.”

The U.S. Board on Geographic Names confirmed the name “Cutts Island” in 1977 and acknowledged its long-time local reference as “Deadman Island.” Although it is certainly possible that Cutts Island was also used as a Native American burial site, the 1857 survey makes several comments about the island with no reference to graves or remains. As stated above, the same surveyor, on the same day, recorded graves on Grave Island. There does not appear to be any documented evidence of graves or human remains on Cutts Island.

What Was There?

Tanglewood Island (the island formerly known as Grave Island / Ka-ka-als) is entirely privately owned today, with a few houses and cottages, and was for many years the site of a prominent boys’ summer camp. The only documented eyewitness account of the Indian graves between 1857 and the 1940s appears in Caroline Perisho’s 1990 book Fox Island: Pioneer Life on Southern Puget Sound:

“Tilson Bixby’s teenage son Ray… one particular day… rowed out to Grave Island… As the boys wandered through the eighteen acres of woods, they found an Indian burial site, complete human skeletal remains wrapped in a blanket and placed in a canoe… Surrounding the wrapped body were… personal tokens, including a rifle which the boys took home with them.”

Ray Bixby (1877–1971) places this event sometime in the early 1890s and suggests that burial structures were still intact at that time. How Perisho received this story is not clear—it may be second-hand—but it adds important detail to what once existed there.

A more general description of Native American funerary practices among the Puyallup and Nisqually peoples appears in the 1940 ethnographic study The Puyallup-Nisqually. It includes detailed accounts of canoe burials suspended in trees, plank-covered ground burials, and the cultural distinctions between inland and saltwater groups regarding burial methods.

“Two forms of disposal were employed, the suspension of the body in a canoe and burial. In the former, the body was wrapped in robes, blankets, etc., placed in the canoe and the whole covered with mats which shed water. It seems that only fishing canoes were used for this purpose, a fact which, if adhered to strictly, would in itself limit this type of disposal to salt water groups. The ends of the canoe were tied to the trunks or branches of adjoining trees or placed in conveniently located forks of adjoining trees. No voluntary mention of placing the canoe between the limbs of a single tree was made, although when suggested the possibility was not denied. No uprights nor frames were ever erected to hold the canoes. The usual height from the ground was between ten and fourteen feet. Persons who had no canoes were bound upon cedar planks which were suspended in the same way. The other mode of disposal was by burial, preferably in stony ground. Above such graves were erected cedar plank sheds with a single peak about two and a half feet above the level of the ground. The planks were arranged with one end in the earth. Such sheds were said to have been designed to protect the grave from rain. In later days they were made of canvas. The inland informants claimed that such burials were employed only by inland or by horse Indians. One informant’s maternal grandfather, who was half Yakima and who bore a Sahaptin name, but who had lived the greater part of his life among salt water groups of Salish, was buried on the Brown Point bluff and a canvas tent erected above the grave. I could not discover whether any of his Sahaptin relatives had been present at the time of disposal.“

A Plot Twist in 1947

Most local histories about Grave Island lean heavily on an April 17, 1947 Seattle Times article, “Lighthouse for Camp.” While nominally about the lighthouse, the article focuses on the boys’ camp built there and includes interviews with Dr. Dick Schultz (the island’s owner) and Ed Erickson. The most-cited paragraphs are:

“As Grave Island, the spot was sacred to the Nisquallys… Ed Erickson… ‘Neighbors of mine over at Sylvan says he saw bones in the trees when he came in ’88’… ‘Fact is, the bulldozer scooped out one grave when we started the pavilion. We found about a quart of beads with it.’”

Dr. Schultz also claimed that the Smithsonian Institution removed all traceable relics from Grave Island prior to 1891.

It is possible Erickson was referring to Ray Bixby’s story, though the 1888 date is early. Many residents of Sylvan Bay likely visited the island.

What Happened to the Funerary Items?

Cecelia Svinth Carpenter addresses the Smithsonian claim directly:

“Several newspaper sources parrot the idea… However, repeated attempts to locate such records have been in vain.”

Research into Smithsonian records shows no evidence of an expedition specifically to Grave Island. Large Smithsonian collecting expeditions did pass through Seattle during the late 1800s and often accepted items brought to them, sometimes with minimal documentation. Considering that the Smithsonian ultimately accumulated remains of more than 30,000 individuals, their archival gaps are enormous. It is certainly possible—though unproven—that some remains or objects from Ka-ka-als reached the Smithsonian.

A revised 2020 Smithsonian Repatriation Case Report includes a 1996 inventory listing:

“A single unassociated funerary object… collected from Fox Island… recommended for return to the Nisqually Tribe…”

All human remains in that same inventory have documented origins, and none were from Fox Island—only the single object. A June 3, 2007 Seattle Times article reported:

“The Smithsonian also will return a funerary object — a spoon made from a horn — that was donated in 1921.”

The Nisqually Tribe does not disclose specific repatriation details, but the 2007 report confirms the return of one funerary object.

The destruction of Native American burial grounds is well documented throughout the United States. Cemeteries were routinely plowed under, removed, or destroyed, and few survived intact. Again, in The Puyallup-Nisqually (p. 201), an account is provided of such an erasure involving the clearing of a burial ground near Point Defiance in 1882—framed, as many narratives of that era were, from the perspective of white settlers.

“The so-called “Puyallup graveyard” was situated on a point of land somewhere between the villages on Commencement Bay and Point Defiance. A creek, citc’acti, ran through it. The ground was solid and covered with a thick growth of crab-apple and willow trees in which the canoes of the dead were suspended. The place remained unmolested until 1882 when a white man, who had discovered that his cattle were grazing among human bones, asked the permission of the Indians to clear it not only of the remains of the dead but of trees and brush so that it might be used for pasture. Permission was granted and he hired young Indians connected with Cushman School to undertake the work and burn the refuse. One of the informants was hired for this.”

How It Became Tanglewood Island

Over the years, several settler names were applied to the island: Hoska (the first non-Native claimant), Ellen’s Island, Grant Island, and Tanglewood Island (likely referencing Hawthorne’s Tanglewood Tales). The 1942 USGS map still shows it as “Grave Island.”

A 1900 Pierce County plat map does not show an owner, but by 1936 the Metsker’s Map lists the “C. L. Hoska estate.” Conrad Hoska (1856–1910) was a well-known Tacoma figure. His 1910 obituary in the Spokane Chronicle noted:

“Mr. Hoska was to have entertained the visiting delegation… at his summer home on Tanglewood Island.”

In 1947, as predicted in the Seattle Times article, the U.S. Board on Geographic Names officially designated the island as “Tanglewood Island” (Decision Nos. 4704–4707). It noted earlier names including Ellen’s Isle, Grant Island, Grave Island, and Hoska Island. The other island labeled “Tanglewood” on the 1942 map later became part of the Fox Island Bridge causeway and is today known as “Towhead Island.”

The Bottom Line

Here is what we know about the small island in Fox Island’s Sylvan/LeMays Bay:

- It was a traditional burial site for local Native peoples.

- Canoe burials suggest individuals of significance may have been interred there.

- Burial features likely survived into the early 1890s (the Bixby account).

- There is no evidence of a mass Smithsonian removal, though individual items (rifle, spoon, etc.) were taken.

- The majority of the graves were most likely removed during the early 1900's when the Hoska summer cabin was built.

- Some burials were still present in the mid-1940s when construction disturbed them.

The broader truth is one of colonial-settler erasure—of the island’s name, history, and cultural significance. Learning, teaching, and listening to what happened on Ka-ka-als is one way to prevent that erasure from becoming complete.

Dogfish note: Although speculative, the circumstantial evidence suggests the graves, remains, and funerary items were most likely removed in the late 1890s or early 1900s when the Hoska summer house was built.