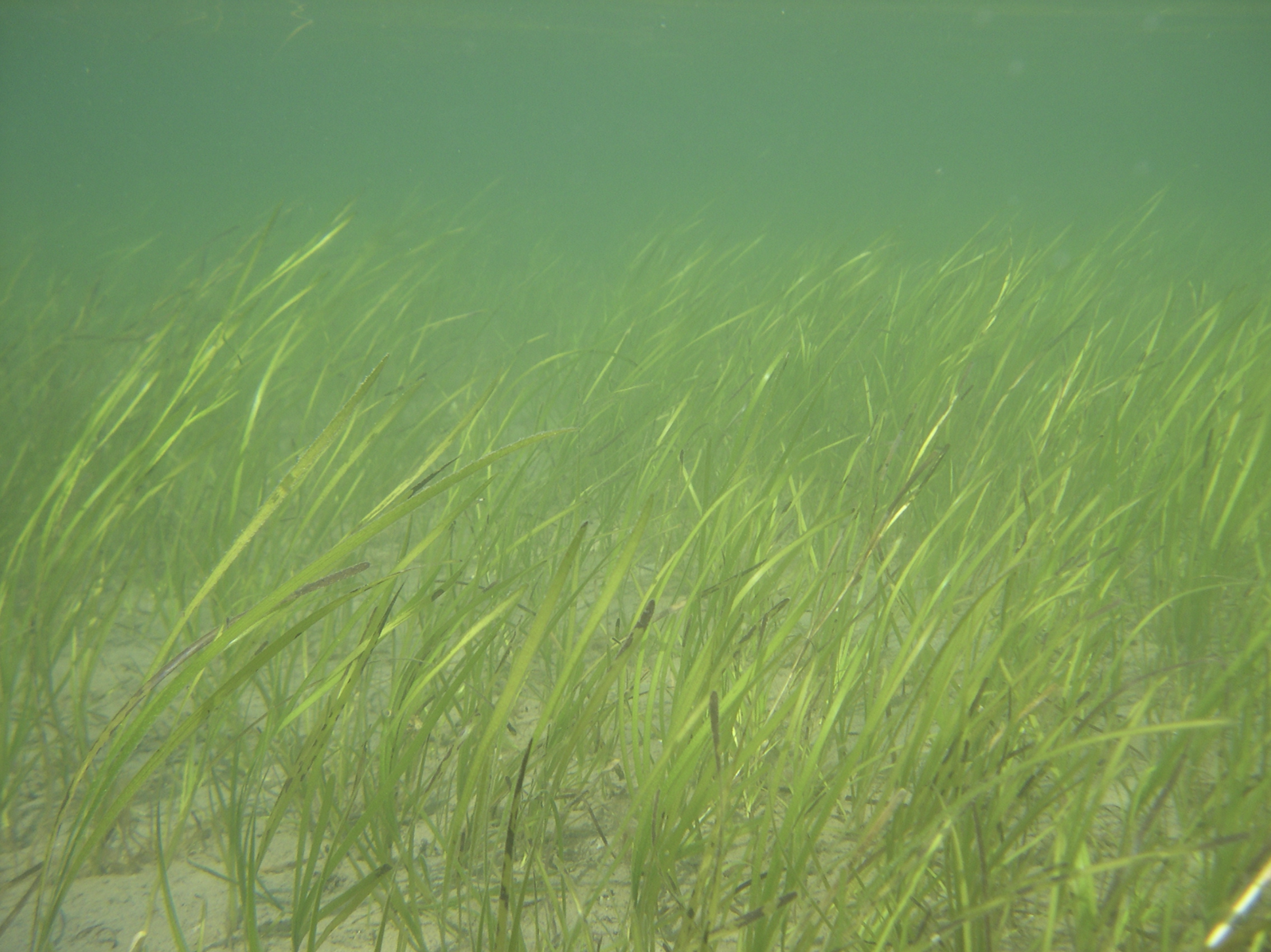

Eelgrass

Why all the fuss about sea grass?

September 2025 (researched and written by The Dogfish)

So why is this marine grass so talked about, regulated around, protected, cursed, and still considered critical in Puget Sound? As Eric Grossman, USGS research geologist and lead for the Coastal Habitats of Puget Sound project, puts it: “It’s difficult to overestimate the importance of Zostera marina, the common eelgrass. It’s fast-growing, adaptive, and is the most widespread flowering marine plant in the Northern Hemisphere, growing in estuaries from subtropical to sub-polar regions.” Eelgrass’s prominence hints at its key role in the unique ecosystem that is Puget Sound.

Eelgrass occurs throughout Puget Sound. Birds and fishes—including juvenile salmon—feed within eelgrass meadows on the rich invertebrate and algal community that grows on and among the blades (some waterfowl also graze directly on eelgrass). Eelgrass beds provide spawning substrate for Pacific herring and nursery habitat for Dungeness crab. They also perform a physical role: slowing currents, dampening waves, stabilizing soft sediments, and reducing shoreline erosion—while offering young salmon refuge from predators as they migrate from rivers to the sea.

Eelgrass beds were severely impacted in the 20th century by altered river flows, pollution, and extensive shoreline modification (armoring, overwater structures, dredging) that accompanied regional population growth and industrialization. Eelgrass needs cool, clear, well-lit water; when nutrients and contaminants fuel algal blooms and turbidity, light declines and photosynthesis suffers. Improvements in wastewater treatment, stormwater control, and shoreline management have helped. According to recent Sound-wide monitoring (2018–2020), overall eelgrass abundance has been relatively stable, though local trends vary.

Eelgrass is a fully marine plant that flowers, fertilizes, produces seeds, and thrives underwater in much the same way as a terrestrial grass. Although this may sound unremarkable, the fact that eelgrass is a true vascular grass sets it apart from most marine flora. In Puget Sound, the majority of plant-like life forms are algae, including large specimens such as seaweeds and bull kelp. Unlike eelgrass, algae are non-vascular and reproduce in a variety of ways—both sexual and asexual—none of which involve the production and fertilization of seeds.

In Puget Sound eelgrass typically occupies the intertidal to shallow subtidal zone—roughly around mean lower low water (MLLW) down to several meters below, depending on water clarity and local slope. In the Hale Passage and Fox Island area, recent surveys mapped eelgrass primarily at or below approximately −1 to −4 feet relative to MLLW (see the Washington DNR ArcGIS interactive map referenced below).

Much like trees in a forest, eelgrass is primarily habitat rather than a direct food source. There are exceptions—various small snails and, most notably, the Pacific Black Brant, which prefers eelgrass as its primary food. Brant (similar in appearance to Canada Geese but smaller and lacking the white “chin strap”) winter in Puget Sound. Canada Geese will occasionally graze eelgrass but, like other waterfowl, primarily forage for the many foods available within eelgrass meadows.

Eelgrass meadows are a forest-like home to a vast array of epiphytes (often algae living on plant surfaces) and small marine animals. Forage fish, such as Pacific herring, shiner perch, and Pacific sand lance, thrive within these meadows and are a primary food source for salmon.

Eelgrass’s role in the life of salmon is more nuanced. Eelgrass beds provide habitat for salmon prey—including juvenile forage fish and small invertebrates—and studies show that juvenile salmon leaving their natal streams rely on eelgrass for refuge from predators, including marine birds. This function is hardest to preserve because juvenile Chinook and Coho depend on extensive meadows and continuous bands of eelgrass during their first year in salt water.

Like much of Puget Sound, Hale Passage supports a broad mosaic of eelgrass beds and meadows. These are critical habitat for the wider ecosystem and are especially important to salmon recovery. Resident (blackmouth) Chinook salmon depend heavily on eelgrass for both forage and protection