The Good News Is...

We're doing better, let's do more.

September 2025 (researched and written by The Dogfish)

I was recently reading The Natural History of Puget Sound Country, a 1991 text on the Puget Sound environment. Several passages stood out as reflecting an early 1990s reality. For example:

“Harbor porpoises, fairly common until the 1950’s, now perhaps gone from Puget Sound.”

Thankfully, this did not turn out to be true. Harbor porpoises have returned and now thrive throughout the Sound. Small groups are common sights around Fox Island and through Hale Passage. The text continues:

“Whales and other cetaceans are uncommon today in the busy waters of Puget Sound; one cannot predict when and where they will appear.”

Whales are certainly unpredictable, but they are not uncommon. Orcas are regularly seen in South Sound, along with occasional gray whales. A pod of orcas moving through Hale Passage often draws throngs of people onto the Fox Island bridge or to the Tacoma DeMolay Nature Preserve spit.

The book also listed sea lions, sea otters, and other marine animals as “all but non-existent” in Puget Sound. Sea otters are slowly recovering—from just 59 individuals in the early 1970s to 2,800 counted in 2019. Although the vast majority of otters in South Puget Sound are river otters, and unless you really know your marine weasels (yes, sea otters are the largest member of the weasel family), you should assume any otter you see is a river otter. Still, there have been a few sightings of a lone male sea otter in Hale Passage in recent years. Sea lions, meanwhile, have recovered so strongly that they are occasiona

The purpose of this narrative is not to say “everything is OK,” but rather to counter the reciprocal narrative, “everything is getting worse.” It’s good to celebrate the wins.

Bald Eagles - a once unimaginable recovery

I work with young people, many of whom have an intense anxiety about the future. While there is no shortage of things in this world to worry about, they often lack awareness of what has improved. For example, they struggle to imagine a world where American bald eagles were not common. Growing up in Washington, I never saw one until I was 16 years old. Today, it’s unusual to spend a day around Hale Passage without seeing at least one.

The recovery of bald eagles—from fewer than 400 nesting pairs in 1963 to over 300,000 individuals and 70,000 nesting pairs estimated during a 2021 survey—is a case study in how collective effort can make things better.

This recovery didn’t happen by accident. It began with the Bald Eagle Protection Act of 1940 and accelerated in the early 1970s with the Endangered Species Act (1973), the banning of DDT, and major efforts not just to preserve but to restore eagle habitat. The wetlands around Warren Creek are an excellent example of preserved habitat that sustains the lifecycles of many species, including at least one breeding pair of bald eagles. Habitat preservation continues today.

Salmon Passages – Bringing the PNW Back Home

It is exciting to be part of ongoing efforts to improve the key environments on which marine birds, mammals, and fish depend. One example is the construction of road and highway salmon passages. At first, they may seem overdone, expensive, and prone to causing traffic delays. But when you see them working, they’re inspiring.

In his book The Good Rain, Timothy Egan writes:

“The Pacific Northwest is simply this: wherever the salmon can get to. Rivers without salmon have lost the life source of the area.”

Damming, polluting, or blocking salmon from their native habitat denies an area its claim to being truly “Pacific Northwest.” While large dams, such as those on the Columbia River, are the most obvious examples, smaller obstructions—especially road culverts—block fish from spawning grounds in numerous ways.

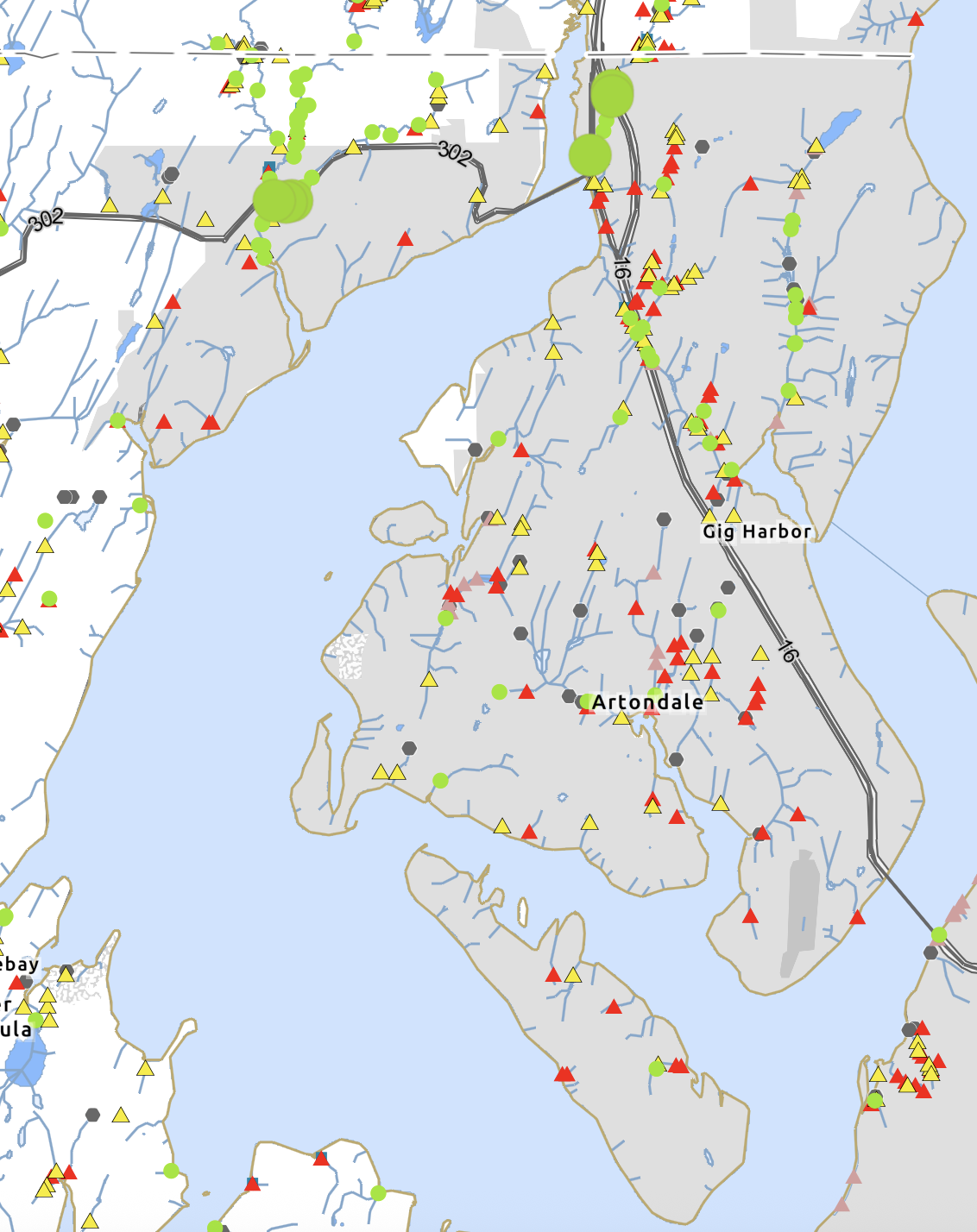

Undersized culverts produce water velocities salmon cannot overcome and often create unmanageable drops. Metal culverts also strip away natural features like vegetation, woody debris, and rocks that salmon rely on for cover when migrating. Washington State’s Fish Passage Program is addressing this by replacing old culverts with wider, naturalized passages that welcome re-established salmon runs.

A common question is: “If salmon always return to the same stream, how does fixing a dead stream help?” Like many “rules,” salmon homing is only mostly true. Studies show 1–15% of returning salmon stray to other waterways, with rates varying by species (low for coho, as high as 15% for ocean-run Chinook). As a result, a renewed waterway can host a spawning run again within just a few years.

It’s important to remember that restoring habitat is never a single action. Salmon recovery depends on multiple measures: fish passages, irrigation canal screening, eelgrass restoration, pollution reduction, hatchery supplements, protection of forage fish, and more. Likewise, marine mammal recovery depends on reduced pollution, restored food sources, noise mitigation, regulations limiting disturbance, and much else.

Beyond Fish and Mammals

It can be difficult—especially for younger people—to picture a time when pollution was rampant across the U.S., including in Washington. For example, carbon monoxide, once a major pollutant, has been reduced by 85% nationwide since 1980 according to EPA data. In many cities, reductions reach 90–95%, largely due to cleaner cars and stricter industrial standards.

In the Puget Sound basin, the number of “unhealthy air days” steadily declined until wildfire smoke began driving increases over the past two decades. Before that, most air pollution came from automobiles.

Water quality has also improved dramatically. Better sewage management has been crucial to restoring both fresh and saltwater health. Not long ago, no one would have considered eating fish from Elliott Bay or the Duwamish River. Today, cleaner water not only makes that possible, but is supporting new growth of plants and animals. Who would have imagined a natural kelp bed thriving among the docks of Seattle? Yet that is exactly what’s happening.

Doing Our Part

As individuals who love Hale Passage, we are vital to re-establishing a more natural ecosystem and helping restore the once-vast populations of plants and animals in this beautiful region. Small actions matter: staying well clear of marine mammals, picking up litter (especially plastics), and honoring shoreline regulations. Waterfront residents can help by avoiding shading of eelgrass beds, not armoring shorelines, and maintaining septic systems properly.

As the Dogfish says

We are in this together and making the world a better place. How can you not love that?